Jellyfish can be found all over the world, from tropical to arctic waters. Jellyfish are beautiful to look at from a safe spot, but if you meet one up close, their tentacles can leave a nasty sting. Here’s everything you need to know about jellyfish at the beach:

What is a jellyfish made of?

Despite their name, jellyfish are not fish (nor are they made of jelly). Jellyfish are actually related to corals and sea anemones, and are part of the phylum cnidocytes. These creatures are actually made up of about 95% water. They do not have brains, blood, or hearts, though they do have nervous systems that help them respond to their surroundings.

How do jellyfish end up on the beach?

Jellyfish go with the flow. They float with the current, which means that if the current comes to shore, jellyfish may come too. Stormy weather and strong winds can also bring jellyfish to shore, and they can end up on the beach. Because they contain so much water, Jellyfish die quite fast after they wash up on a beach.

How does a jellyfish sting?

Jellyfish don’t generally intend to sting humans. They mostly use their stinging tentacles to catch and eat their dinner. Still, jellyfish do sting people from time to time, usually by brushing against swimmers, surfers, or other water recreation enthusiasts. It’s also possible to be stung by a dead jellyfish that has washed up on the shore, so always watch your step on the beach.

Jellyfish stings are painful, but in most cases, they are mild and are not too serious.

Normally, they will cause red marks, tingling, itching, or numbness. Jellyfish stings cause more harm in people with weak immune systems, elderly people, and children.

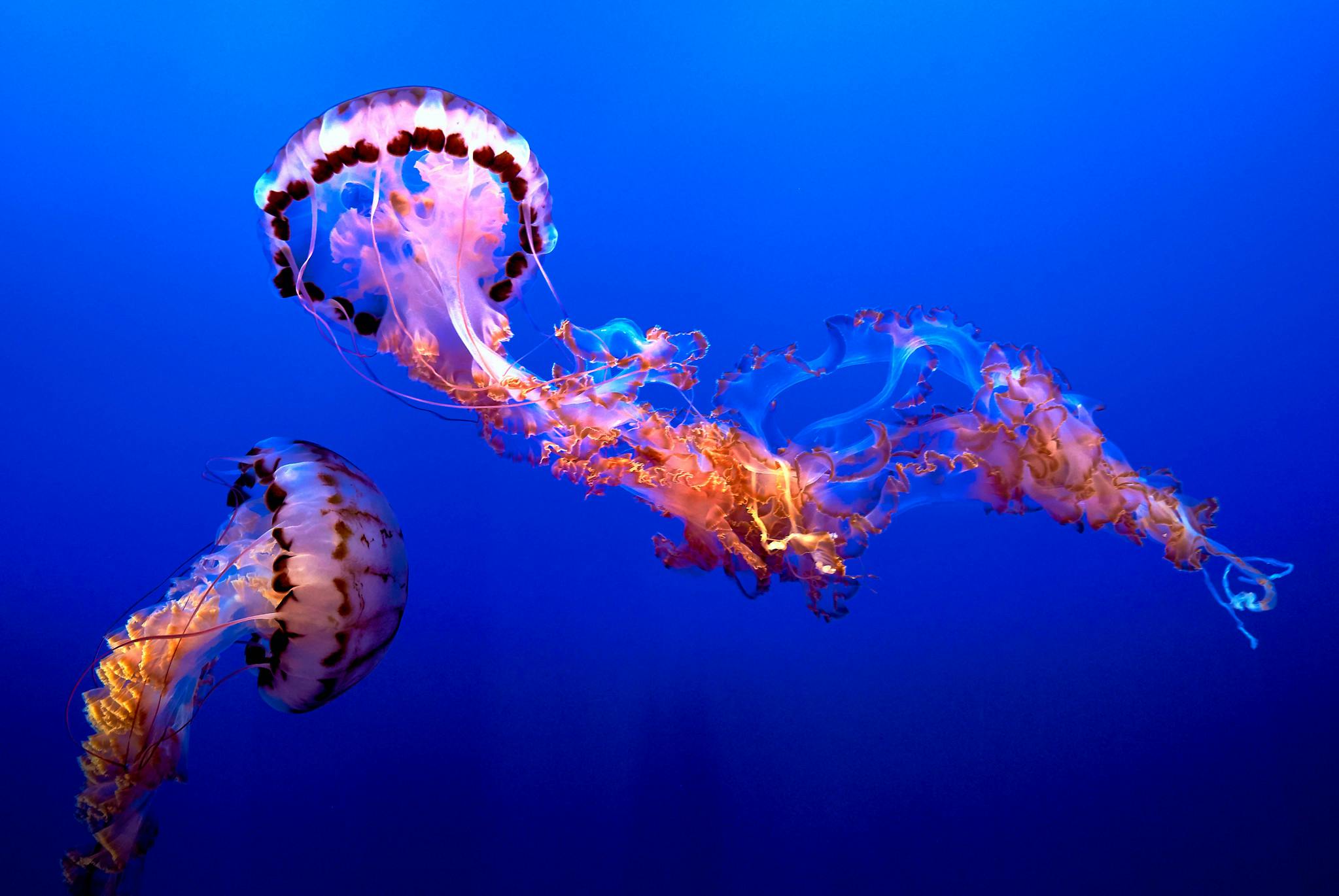

Only some jellyfish stings, such as those from Box Jellyfish (the most deadly), Lion’s Mane Jellyfish, and Sea Nettle, can be very serious. The more dangerous jellyfish species live in Australia, the Philippines, the Indian Ocean, and the central Pacific Ocean. Portuguese Man-of-War are not technically jellyfish. They are actually colonial organisms made up of polyps. Nevertheless, they can deliver painful stings.

Climate change has caused rising ocean temperatures, which are changing where certain dangerous jellyfish can be found. The Portuguese Man-of-War has increasingly been spotted around Canada’s east coast, in Nova Scotia, and area where they are not native.

How can you prevent jellyfish stings?

Beaches in some countries, have jellyfish presence indicators, like like JellyWatch, and some beaches (such as those in Israel), post warning signs and provide digital tools that let people know if there are jellyfish in the waters, and in what quantities. Here are four ways you can prevent jellyfish stings:

1. Use caution when swimming during jellyfish season, or don’t swim at all

Jellyfish season will differ depending on your location. For example, in Australia’s coastal waters, Box Jellyfish are often found from October to May during the country’s wet season. Do your research about jellyfish season before you head to the beach.

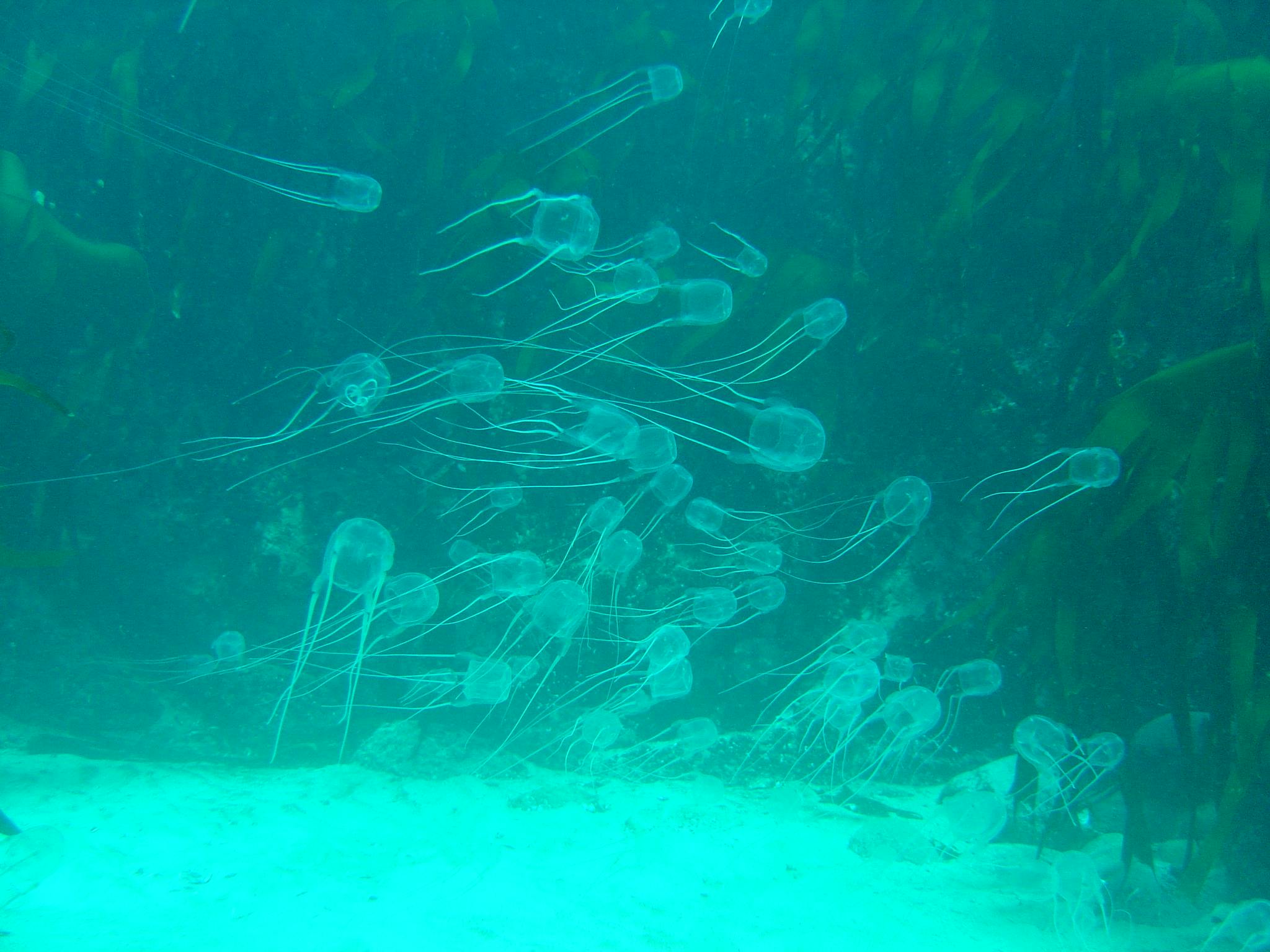

Avoid the water when there are a lot of jellyfish present, such as during a jellyfish bloom. Always survey your surroundings when you arrive at the beach. Seeing jellyfish that have washed up on the beach may be an indicator of jellyfish in the water.

Jellyfish are often present on or near the shore after heavy rain, windy weather, or warmer temperatures.

2. Swim at beaches with lifeguards

Lifeguards will usually make beachgoers aware if jellyfish currently pose a threat to swimmers. Some beaches will post signs or flags. A purple sign indicates dangerous marine life, such as jellyfish. You can also get information from locals or health officials before entering the water.

3. Protect yourself with a wet suit, a protective suit, or jellyfish repellent

Many diving stores carry “stinger suits” or “dive skins” made of thin protective fabrics like Lycra, Spandex, Nylon, or Polyester. Stinger suits allow water to filter through the fabric, but will not let even tiny jellyfish to pass through.

For areas with large populations of dangerously poisonous jellyfish, jellyfish repellent may be a good option. Jellyfish repellent is able to protect you against dangerous jellyfish, like Box Jellyfish and Sea Nettles. These repellants work by tricking jellyfish into thinking the wearer is also a jellyfish, which prevents them from stinging in defence. Jellyfish repellent also has a built-in failsafe: an extract of plankton that helps to block the creature’s sting sensor.

4. Know how to spot a jellyfish

You can often recognize a jellyfish by its tentacles floating on the water. A tentacle that is no longer attached to the jellyfish, can still deliver a potent sting. Immediately leave the water if you see something you suspect to be a jellyfish or tentacle.

Jellyfish can be big or small, clear or colourful. Jellyfish larvae are tiny and much more difficult to spot. Jellyfish repellant will protect you against even larvae and very small jellyfish.

On shore, a dead jellyfish may look like a balloon, plastic bag, or shell from far away. Some jellyfish have extremely long tentacles, so if you see anything that could potentially be a jellyfish on the beach, stay far away.

What can you do if you get stung by a jellyfish?

You may have heard the myth that applying urine to a jellyfish sting is able to counteract the venom, but there is no scientific basis for this “remedy” and it can sometimes actually make the sting hurt more, or make the venom more powerful. Here’s what to do if you’re stung by a jellyfish:

1. Rinse the sting with seawater or create a paste of baking soda and seawater to get rid of the tentacles. If you’re able to, bathe the area in heated tap water or take a warm shower.

2. Remove any leftover tentacles with a dry towel. If the tentacles are difficult to remove, try coating them with shaving cream, then shaving them off with a razor or credit card. Protect your hands with gloves if possible.

3. Protect the site of the sting. Avoid pressure and contact with sand.

4. Taking pain relievers like ibuprofen or applying antihistamines or steroid creams (like cortisone) can lessen the pain, itching, and swelling. In Australia, most lifeguard teams are equipped with morphine and antivenoms to treat the nastier stings from Down Under.

Although serious allergic reactions or anaphylaxis after a jellyfish sting are uncommon, they are cause to see a doctor. If you have these symptoms, seek medical attention:

- Numbness or dizziness

- Swollen lips and eyes

- Developing a rash

- Tightness in your chest

- Trouble breathing or swallowing

- Pain that doesn’t lessen after caring for the sting and taking pain relievers

- Abdominal pain or cramping muscles

- Nausea and vomiting

- Signs of shock, such as pale skin, quick pulse, or passing out

- It’s also possible for jellyfish stings to become infected after the fact. Symptoms of infection include:

- Increasing pain

- Redness or red streaks leading away from the injury

- Swelling

- Pus

- Warmness of the area

- Fever

- Chills

Jellyfish populations may be increasing globally, and it seems that human influence on the environment may be to blame. Jellyfish blooms happen periodically, but in recent decades, some jellyfish species are blooming in regions where they are not native. Water pollution and warm oceans may also be causing populations to grow, since jellyfish are able to survive in contaminated water and in dead zones with little oxygen, and they seem to breed best in warm water as well.

Only a small number of jellyfish will actually end up coming into contact with swimmers, and many of them do not give serious stings.

They’re definitely no reason to fear the water! There are even a number of jellyfish that sting very mildly or do not sting at all, such as Pleurobrachia Bachei (more commonly known as sea gooseberries), or Aurelia Aurita (also called the moon jelly).

In fact, swimming with jellyfish is a popular tourist activity in some places. In the famous Lake Palau in the Philippines, you can swim with Golden jellyfish and Moon jellyfish. Swimming with jellyfish just may give you a new perspective on these beautiful and fascinating creatures.